I worked for Tyson Foods one summer in the late 90s at the cold storage distribution facility in Russellville, Arkansas. The coaches at Arkansas Tech University, where I played strong safety for the Wonder Boys, set it up so a small band of us who were sticking around town for the summer were able to make a little money and provide some seasonal help.

I remember that summer with a certain nostalgia. And even though I push buttons on a keyboard for a living now, there are afternoons when I daydream about stacking boxes of chicken onto trucks and running pallet jacks up and down the docks.

The group that went to work at Tyson that summer was racially diverse, and I remember wondering how we’d be received by the shift we joined. Alas, we soon realized we were all there to work. This is what bound us, and what binds us still.

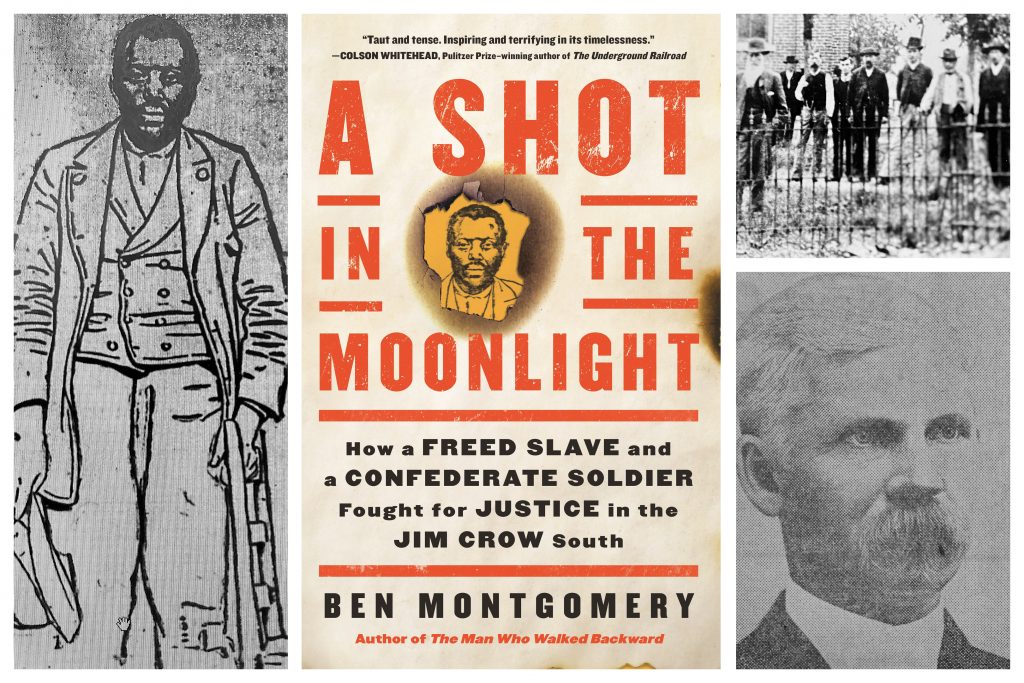

In that spirit, in the closing days of Black History Month, I give you an excerpt from my new book, “A Shot in the Moonlight.” It’s the true story of George Dinning, a man born into enslavement, who, once emancipated, set to work.

He was a peaceful man who minded his own business. He invested his time and energy into about 125 acres of fertile farmland in southern Kentucky, land he owned outright, until a gang of white men showed up one night in January 1897 to try to take it.

January 21, 1897

When the guns fell silent and the white men took cover, George Dinning burst out the back of his little wooden house, wearing only his undergarments. He ran through the frigid January air, and when he reached the tall grass of a nearby field, he hurled himself down flat on his back, his lungs heaving, his breath visible and rising beneath a moon almost full and what seemed to be a million stars poking through a smoky blue-black midnight sky. He lay still and quiet and listened to the men’s voices coming from the north, beyond the house. They sounded at first as though they were in a state of consternation, but the voices grew distant as time slid by, suggesting retreat.

When he could no longer hear the voices over the heartbeat in his own ears, he sat up slowly, looked around, then darted across the field toward his house. His wife met him at the door with his boots, his heavy coat, and his hat, and he dressed quickly, without saying much, then turned away from the humble home he had built with his own hands, the only home his children had ever known, the home he had defended, and he disappeared into the darkness.

He ran, crashing through the near-freezing vegetation of southwestern Kentucky in close proximity to the Red River, which rolled silently west toward the Cumberland. He remembered the sight of his house surrounded by white men with guns and he tried to puzzle out in his mind the last few minutes, for what had just happened would determine which action he next chose. Who were those men? And whom among his neighbors could he trust?

He made his way first to the farm of Gib Hackney, a white man—a good man, he thought, a friend—who lived a half mile away, near the Tennessee state line. From the nighttime shadows Dinning bellowed, then waited, but he saw no light and heard no sound. He bellowed again and the same silence followed, so he turned and ran.

He cut through field and forest, and the sounds of his footfalls carried through the cold night. A mile away, at Price’s Mill, he came upon the home of Zack Murray, another white man. Dinning called out to him, and Murray appeared in the doorway with a lantern. Murray held the lantern up to the heaving Black man standing before him and examined Dinning in the firelight. He first noticed the shotgun in Dinning’s grip, one of two loads spent. He then saw blood oozing down Dinning’s face, and then the wellspring: a gunshot wound in Dinning’s forehead, as big around as the tip of his finger. He examined Dinning’s arm and saw where his undershirt had torn and saw a wound about a quarter inch deep and an inch and a half long.

Dinning followed Murray inside. When he’d caught his breath, he explained to his neighbor the evening’s events, lantern light dancing on the walls around them:

He had eaten dinner at dusk. He had hauled some wood in. He had stoked the fire. His wife, Mollie, and children had climbed into bed. There was the baby, four months old; Emma, three years; Nannie, four years; Mertrude, six years; George Jr., eight years; Viola, ten years; and Eva, twelve years old.

He had drifted into a deep sleep and woke when Mollie shook him. He had heard the dog barking outside, then voices. Then he heard someone call his name, “George!”

The men accused him of stealing from smokehouses, and he protested, said upstanding white folks would speak on his behalf. That was when the bombs came. He thought they were bombs, or dynamite, because they came from above and sounded like someone had cast handfuls of gravel on the floor. Murray tried to set him straight, said he and his whole family would be dead if somebody had thrown dynamite into his little house.

Whatever it was, Dinning told Murray that he grabbed his shotgun and started up the stairs, and just as he passed a window, he felt a sharp pain in his arm and looked down and saw his own blood. He rushed upstairs and threw open the window at the foot of his daughter’s bed. He felt a great pain in the center of his forehead, and he pointed his gun at what seemed to be a yardful of men down below. He squeezed and the blast from his muzzle lit the night. The gunshot seemed to stop time for a split second, and a silence rushed over him, a silence that preceded a great deafening hail of explosions, of flying bullets, bullets flying over the heads of his children.

Murray asked if he’d recognized anybody. Dinning didn’t know. Didn’t think so.

The two men sat until 5 a.m., and Dinning told Murray he’d better head back to the house to check on his family, to face whatever might come. Dinning fetched his shotgun and headed toward the place he’d called home for fourteen years, but his friend Bob Lucas intercepted him a hundred yards away. Bob was a farmer, Black, younger than Dinning by eight years or so, and he lived nearby. In fact, the men who’d come the night before had asked Dinning if he knew where Bob Lucas was. He didn’t, he said. The men told him they were looking for Bob Lucas, too, and now here he was, coming down the road before sunup, carrying devastating news.

One of the men had been hit by George Dinning’s birdshot, Bob Lucas told him, in the cheek and neck and shoulder. Had fallen from his horse in front of George Dinning’s house. Had spilled blood in George Dinning’s yard. Had passed in the night, George Dinning’s name on his tongue.

“You shot Jodie Conn,” said Bob Lucas. Dinning knew Conn, had done work for him. Had no problem with the man. Hadn’t known he was there that night. Conn was a wealthy farmer from the next county over, Logan. He was the thirty-two-year-old scion of the Conn family. And they would soon prepare his grave.

There was no time to go home, not under the circumstances. The whites would be bent on revenge. He had to trust that they wouldn’t harm his babies.

———————————–

Without her husband, and surrounded by the gun-hung whites of southern Kentucky, what choice did Mollie have? She did not protest that frigid January evening, though she was frightened and worried about her sick daughter. She quietly put Hermann on one horse and threw several featherbeds in front of him, over the horse’s shoulders. She lifted Eva up to him. The girl was ill and shaken. With her baby in her arms, Mollie mounted their second horse and helped the other children up behind her.

At sundown, after one last look, the family started down the frozen road. They hadn’t eaten that day, on account of the chaos. “I was so badly frightened when I left, that I did not take time to put wrappings on myself or children,” Mollie would later say. Once they’d gotten a few miles away, charitable Black families carried food out to the road and handed it up to the outcasts. They rode until they reached the Tennessee line, and beyond that, the home of Mollie’s brother.

Mollie and the children were long out of sight when the white men returned, sloshed out kerosene, and set fire to the main house, to the smokehouse, to the barn, and to the life-giving bottomland fields upon which she and her husband had toiled for fourteen years, from which they’d earned a hard and honest living as free people, to which they would never return. They wouldn’t have smelled the first wafts on the night air of their own possessions catching fire—their threadbare clothes, their woodware, their feather beds, their schoolbooks. They wouldn’t have heard the footfalls of the guffawing and lawless jackboots hustling across the spiny burdock, or the crackle and lurch of the cabin behind them as the fire came alive and consumed it and, hungry still, licked at the curling Kentucky sky.